|

||||||||

| Tracks 1-16 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Select Excerpts from the Interview

Track 2

![]() DR LOVE: Can you talk about the results of the BCIRG 006 study

comparing AC docetaxel to AC

DR LOVE: Can you talk about the results of the BCIRG 006 study

comparing AC docetaxel to AC ![]() docetaxel/trastuzumab to TCH

(docetaxel/carboplatin/trastuzumab)?

docetaxel/trastuzumab to TCH

(docetaxel/carboplatin/trastuzumab)?

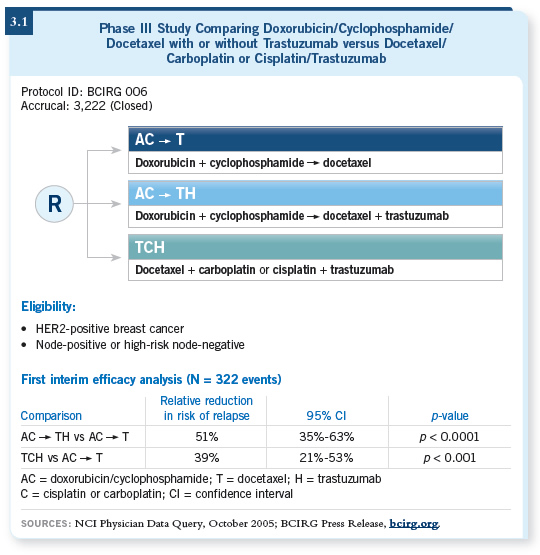

![]() DR TRIPATHY: Both of the trastuzumab-containing regimens lowered the risk

of recurrence (Slamon 2005; [3.1]), and they’re not statistically different from

each other. The reduction is numerically greater in the AC docetaxel and trastuzumab arm compared to the nonanthracycline arm. But longer follow-up

is needed to get the statistical power to find which one wins out.

DR TRIPATHY: Both of the trastuzumab-containing regimens lowered the risk

of recurrence (Slamon 2005; [3.1]), and they’re not statistically different from

each other. The reduction is numerically greater in the AC docetaxel and trastuzumab arm compared to the nonanthracycline arm. But longer follow-up

is needed to get the statistical power to find which one wins out.

![]() DR LOVE: It’s approximately a 51 percent reduction with the anthracycline,

and it’s 39 percent with TCH. Dr Slamon showed the confidence intervals

overlapping, yet a lot of people are looking at those numbers, saying, “Hmm.

It looks as if TCH is not quite as good.” Is that the way you see it?

DR LOVE: It’s approximately a 51 percent reduction with the anthracycline,

and it’s 39 percent with TCH. Dr Slamon showed the confidence intervals

overlapping, yet a lot of people are looking at those numbers, saying, “Hmm.

It looks as if TCH is not quite as good.” Is that the way you see it?

![]() DR TRIPATHY: I must admit, I do see it that way as well. These are very early

results, but we tend to project over time how these curves may continue to

diverge. However, we all have to be cognizant that we’ve been wrong before

and we must wait for all the data.

DR TRIPATHY: I must admit, I do see it that way as well. These are very early

results, but we tend to project over time how these curves may continue to

diverge. However, we all have to be cognizant that we’ve been wrong before

and we must wait for all the data.

But it’s a totally legitimate interpretation. After all, we have to make the best decisions we can for our patients. Sometimes, as an oncologist, you have to take your intuitions about what you sense might be better, even though the statistical rules don’t apply. Here we have a 12-point difference between the hazard reductions. Although that’s not statistically significant, I believe we need to keep it in mind.

Track 4

![]() DR LOVE: What about the possibility of using adjuvant trastuzumab

monotherapy without chemotherapy?

DR LOVE: What about the possibility of using adjuvant trastuzumab

monotherapy without chemotherapy?

![]() DR TRIPATHY: Theoretically, trastuzumab monotherapy may be a reasonable

approach.

DR TRIPATHY: Theoretically, trastuzumab monotherapy may be a reasonable

approach.

Remember that in the HERA study, a 50 percent reduction in recurrence was seen in all patient groups, which included all comers (Piccart-Gebhart 2005). But keep in mind that as a requirement of the HERA study, all patients received prior chemotherapy. We know that synergy exists between chemotherapy and trastuzumab, so we could argue that trastuzumab works best in the context of chemotherapy.

Although I would guess that trastuzumab monotherapy would reduce recurrence, we don’t have any data to support that. Sometimes extrapolations require too much speculation, and I believe the leap to trastuzumab monotherapy is one of those situations.

Trastuzumab monotherapy would be good to include in a trial if we could identify an appropriate patient population. We currently have options for chemotherapy regimens that are nontoxic, like some of those used in the HERA trial.

Dr Heikki Joensuu has studied vinorelbine followed by FEC ( Joensuu 2006), opening the door to studies of agents with preclinical synergy and great activity in the advanced setting. I would advocate a trial, maybe with vinorelbine plus trastuzumab in one arm and trastuzumab alone in another arm.

![]() DR LOVE: What about a taxane alone with trastuzumab?

DR LOVE: What about a taxane alone with trastuzumab?

![]() DR TRIPATHY: That is a little more reasonable, although again, we do not

have the data. Technically, the HERA study would have allowed that, but I

don’t think there were any patients who received paclitaxel alone. In talking

about where one would draw the line, taxane alone with trastuzumab, in my

mind, would be reasonable.

DR TRIPATHY: That is a little more reasonable, although again, we do not

have the data. Technically, the HERA study would have allowed that, but I

don’t think there were any patients who received paclitaxel alone. In talking

about where one would draw the line, taxane alone with trastuzumab, in my

mind, would be reasonable.

Track 7

![]() DR LOVE: What about the delayed use of trastuzumab? For example,

how would you approach a patient with HER2-positive disease who was

treated six months or a couple of years ago but didn’t receive trastuzumab?

DR LOVE: What about the delayed use of trastuzumab? For example,

how would you approach a patient with HER2-positive disease who was

treated six months or a couple of years ago but didn’t receive trastuzumab?

![]() DR TRIPATHY: This is a dilemma. You have to decide one way or the other. If

the patient comes to you, then you can’t just throw up your arms and say you

don’t know. My approach is to individualize therapy.

DR TRIPATHY: This is a dilemma. You have to decide one way or the other. If

the patient comes to you, then you can’t just throw up your arms and say you

don’t know. My approach is to individualize therapy.

We know that in both the HERA study and the North American studies (Piccart-Gebhart 2005; Romond 2005), the hazard rate in the entire population was still pretty high at two and three years — around 10 percent per year. Now, the question is, does the risk reduction still apply two years out? That we don’t know.

I can make an analogy with hormonal therapy. I was surprised when the data came out for patients who had been on tamoxifen for five years and were then randomly assigned to placebo versus letrozole (Thürlimann 2005).

Even when initiating hormonal therapy after five years, approximately a 40 percent reduction was still evident, which is about what we expect of hormonal therapy anyway. So at least in the case of hormonal therapy, it looks as though the odds reduction is preserved whether treatment is given up front or much later.

Extending that to trastuzumab, patients at average risk would still have an annual reduction in hazard ratio of about five percent per year. So that would be 10 percent over two years and maybe even more as time goes on. We have to realize that even two or three years out, an odds reduction is likely.

Again, this is where you need to tailor treatment. For a patient with node-negative disease who is a borderline candidate, I would use trastuzumab up front or maybe six months out.

For patients with two or three nodes, I believe it’s appropriate to consider trastuzumab even two years out. I know that’s a stretch, but at least it is based on data on annual hazards and some extrapolations of the activities of other drugs.

![]() DR LOVE: How about beyond two years — say, three or four years?

DR LOVE: How about beyond two years — say, three or four years?

![]() DR TRIPATHY: Again, I believe it’s reasonable. We don’t have hazard rates that

far out. Right now, we have them as far as three years on the longest-running

NSABP study (Romond 2005). Keep in mind that every year we will have

more data on the annual hazards.

DR TRIPATHY: Again, I believe it’s reasonable. We don’t have hazard rates that

far out. Right now, we have them as far as three years on the longest-running

NSABP study (Romond 2005). Keep in mind that every year we will have

more data on the annual hazards.

Currently I would say two, two and a half years is my limit. But a year from now, when we will have more data, I believe we can feel more comfortable. So it’s a moving target, and we have to stay tuned.

Track 8

![]() DR LOVE: What are your thoughts about dose-dense AC

DR LOVE: What are your thoughts about dose-dense AC![]() paclitaxel?

paclitaxel?

![]() DR TRIPATHY: The mathematical theory behind dose-dense chemotherapy

is elegant. The idea is that because of the growth shape of the so-called

Gompertzian curve, administering drugs in closer proximity in a dose-dense

fashion would yield more tumor kill. When growth factors became available,

we could test this.

DR TRIPATHY: The mathematical theory behind dose-dense chemotherapy

is elegant. The idea is that because of the growth shape of the so-called

Gompertzian curve, administering drugs in closer proximity in a dose-dense

fashion would yield more tumor kill. When growth factors became available,

we could test this.

Dose-dense AC ![]() paclitaxel was better than an every three-week schedule

(Citron 2003). But over time, that difference has not been as great, and the

survival difference is now marginal (Hudis 2005). I still think it’s a superior

regimen, but the reason for that is unclear.

paclitaxel was better than an every three-week schedule

(Citron 2003). But over time, that difference has not been as great, and the

survival difference is now marginal (Hudis 2005). I still think it’s a superior

regimen, but the reason for that is unclear.

Data in the metastatic and neoadjuvant settings tell us that a weekly versus every three-week paclitaxel schedule is better. It’s better tolerated and the effectiveness is better, certainly in terms of disease-free survival. An important question is whether the AC part of it needs to be dose dense. In the European epirubicin/cyclophosphamide studies, dose density didn’t seem to be a factor.

One could argue that maybe you could administer AC every three weeks followed by paclitaxel weekly, which is the way it was administered in the adjuvant trastuzumab trials. Because dose dense is a reasonably safe regimen — the toxicity is about equivalent — my practice is to use it in HER2-negative cases. I believe it is a better regimen.

Track 9

![]() DR LOVE: What is the next generation of clinical trials that will focus on

HER2-positive disease?

DR LOVE: What is the next generation of clinical trials that will focus on

HER2-positive disease?

![]() DR TRIPATHY: We’d like to improve the odds reduction and use drugs that

target other aspects of the HER2 pathway. A leading candidate is lapatinib,

a dual HER1 and HER2 kinase inhibitor that also inhibits the same target,

HER2, but in a different way.

DR TRIPATHY: We’d like to improve the odds reduction and use drugs that

target other aspects of the HER2 pathway. A leading candidate is lapatinib,

a dual HER1 and HER2 kinase inhibitor that also inhibits the same target,

HER2, but in a different way.

It works on the cytoplasmic kinase domain, which is part of the signaling initiator. Some early data show a higher response rate when you combine lapatinib and trastuzumab. We already know from early pilot trials that previously untreated patients with HER2-positive disease show good response rates with lapatinib.

I’m not enthusiastic about this trend for trials of other chemotherapies because we need to build on trastuzumab first. I’m concerned that we’re simply adding more and more therapies without making an effort to find out who in particular needs them. I don’t want to see a trend toward every adjuvant regimen involving 20 drugs. I don’t believe that’s the way we need to go.

![]() DR LOVE: What about clinical trials evaluating bevacizumab with trastuzumab?

DR LOVE: What about clinical trials evaluating bevacizumab with trastuzumab?

![]() DR TRIPATHY: Bevacizumab with trastuzumab is a reasonable combination,

again with the caveats I mentioned. I would prefer to try to isolate the patients

who will benefit, but without that, I do believe it’s reasonable. Some pilot

studies also show that the bevacizumab/trastuzumab combination is safe and

active (Ordonez 2006). We have no randomized studies yet, but I believe that

would be a reasonable place to look.

DR TRIPATHY: Bevacizumab with trastuzumab is a reasonable combination,

again with the caveats I mentioned. I would prefer to try to isolate the patients

who will benefit, but without that, I do believe it’s reasonable. Some pilot

studies also show that the bevacizumab/trastuzumab combination is safe and

active (Ordonez 2006). We have no randomized studies yet, but I believe that

would be a reasonable place to look.

Track 12

![]() DR LOVE: Can you discuss the ECOG-E2100 trial, which showed an advantage

to adding bevacizumab to paclitaxel in the first-line metastatic setting?

DR LOVE: Can you discuss the ECOG-E2100 trial, which showed an advantage

to adding bevacizumab to paclitaxel in the first-line metastatic setting?

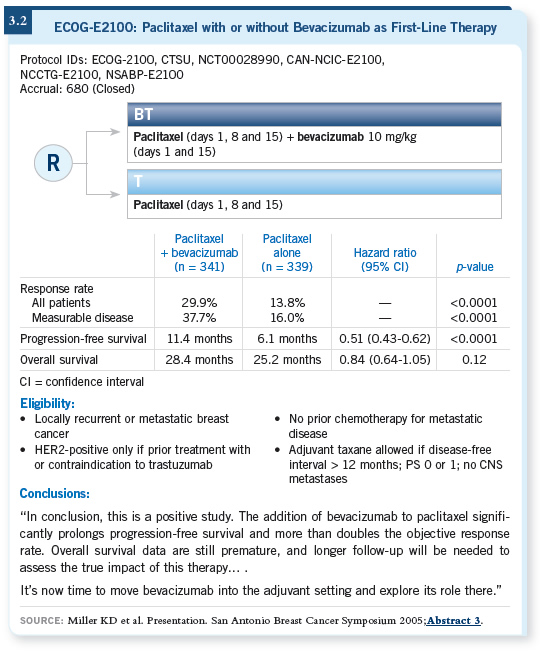

![]() DR TRIPATHY: The main endpoint, progression-free survival, was significantly

prolonged with the combination (Miller 2005c; [3.2]). The hazard

rates indicate a more robust improvement than we’ve seen with single chemotherapy

compared to chemotherapy doublets.

DR TRIPATHY: The main endpoint, progression-free survival, was significantly

prolonged with the combination (Miller 2005c; [3.2]). The hazard

rates indicate a more robust improvement than we’ve seen with single chemotherapy

compared to chemotherapy doublets.

Much attention has been given to the survival difference, which was statistically significant when initially presented at ASCO (Miller 2005c) but was not significant at the next two presentations at ECCO and San Antonio (Miller 2005a, 2005b). It’s important to remember that the number of events was nowhere near what was projected for that analysis.

So although survival is an important endpoint, I don’t believe the trial had enough power to demonstrate whether a survival advantage exists.

In the end, data on overall survival will be important in deciding whether to use it. But right now, you have to go with the data on progression-free survival.

![]() DR LOVE: How has that played out in your own practice?

DR LOVE: How has that played out in your own practice?

![]() DR TRIPATHY: I have tried to practice the way the trial was designed, using

bevacizumab for patients only as first-line therapy. I use it with paclitaxel, and

I tend to reserve it either for patients who are symptomatic or for those who

may not be symptomatic but whose disease trajectory is such that I would

predict they might become symptomatic soon. It’s a judgment call.

DR TRIPATHY: I have tried to practice the way the trial was designed, using

bevacizumab for patients only as first-line therapy. I use it with paclitaxel, and

I tend to reserve it either for patients who are symptomatic or for those who

may not be symptomatic but whose disease trajectory is such that I would

predict they might become symptomatic soon. It’s a judgment call.

In terms of whether or not we might want to generalize this and combine bevacizumab with other chemotherapeutic drugs, I believe that’s a reasonable consideration. For patients who have already received a taxane in the adjuvant setting, should we use a drug like capecitabine? I believe it would be reasonable.

Track 14

![]() DR LOVE: What are your thoughts about nanoparticle albumin-bound

(nab) paclitaxel?

DR LOVE: What are your thoughts about nanoparticle albumin-bound

(nab) paclitaxel?

![]() DR TRIPATHY: Nab paclitaxel is a good alternative to paclitaxel and seems to

be a more active drug, but I don’t believe we know the optimal schedule yet

for that drug. When it was tested on an every three-week schedule, it brought

a little more neuropathy than standard paclitaxel (O’Shaughnessy 2003).

DR TRIPATHY: Nab paclitaxel is a good alternative to paclitaxel and seems to

be a more active drug, but I don’t believe we know the optimal schedule yet

for that drug. When it was tested on an every three-week schedule, it brought

a little more neuropathy than standard paclitaxel (O’Shaughnessy 2003).

Some more recent data evaluating weekly schedules of 100 mg/m2 or 125 mg/m2per week suggest less neurotoxicity (O’Shaughnessy 2004). For a patient who is symptomatic and you want to see a response, nab paclitaxel is a better choice, quite frankly, and I’m using it.

Can you extend that to combine it with trastuzumab for HER2-positive disease or with bevacizumab? You probably could, but I would likely wait for the data.

![]() DR LOVE: When you’ve used it in your practice, what kind of dose and

schedule have you utilized?

DR LOVE: When you’ve used it in your practice, what kind of dose and

schedule have you utilized?

![]() DR TRIPATHY: I’ve used both of the tested dosing schedules, although the

standard 260 mg/m2 every three weeks is probably what I use more often. For

patients who are very concerned about neurotoxicity, I tend to use it at the

lower dose — 100 mg/m2 weekly on days 1, 8 and 15 of a 28-day schedule.

DR TRIPATHY: I’ve used both of the tested dosing schedules, although the

standard 260 mg/m2 every three weeks is probably what I use more often. For

patients who are very concerned about neurotoxicity, I tend to use it at the

lower dose — 100 mg/m2 weekly on days 1, 8 and 15 of a 28-day schedule.

![]() DR LOVE: How has that played out in your practice in terms of the shorter

infusion time and the lack of need for premedication?

DR LOVE: How has that played out in your practice in terms of the shorter

infusion time and the lack of need for premedication?

![]() DR TRIPATHY: I can’t comment much on my individual practice because we’re

fortunate in that we don’t see patients with that much comorbid illness. Both

are advantages, but I believe the big advantage is that you don’t have to use

steroids. Not only do they cause nuisance-type side effects, but in patients with

diabetes, they also cause major problems. So that alone is a big advantage.

DR TRIPATHY: I can’t comment much on my individual practice because we’re

fortunate in that we don’t see patients with that much comorbid illness. Both

are advantages, but I believe the big advantage is that you don’t have to use

steroids. Not only do they cause nuisance-type side effects, but in patients with

diabetes, they also cause major problems. So that alone is a big advantage.