|

||||||||

| Tracks 1-19 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

EDITOR’S NOTE: This interview focuses on a recent survey of 12 clinical investigators for a recent Breast Cancer Think Tank. For more information, go to BreastCancerUpdate.com/thinktank

Select Excerpts from the Interview

Track 2

![]() DR LOVE: Can you talk about the use of sequential tamoxifen/aromatase

inhibitors versus up-front aromatase inhibitors in the adjuvant setting?

DR LOVE: Can you talk about the use of sequential tamoxifen/aromatase

inhibitors versus up-front aromatase inhibitors in the adjuvant setting?

![]() DR CARLSON: The different methods of using aromatase inhibitors or incorporating

them — initial aromatase inhibitor therapy versus sequential after two

to three years of tamoxifen versus extended after five years — have never truly

been studied in a randomized fashion, one against another. The BIG 1-98 trial

(Thürlimann 2005) will give us the first look at that sort of comparison.

DR CARLSON: The different methods of using aromatase inhibitors or incorporating

them — initial aromatase inhibitor therapy versus sequential after two

to three years of tamoxifen versus extended after five years — have never truly

been studied in a randomized fashion, one against another. The BIG 1-98 trial

(Thürlimann 2005) will give us the first look at that sort of comparison.

The real question is whether tamoxifen does something to prime the breast cancer cells and cause the aromatase inhibitor to be more effective. Or, rather, is it that the population of women and the characteristics of their breast cancer change over time in a way that would make the aromatase inhibitors — or any hormonal therapy — more effective?

I believe a substantial amount of data exists to support the selection bias theory that the population of breast cancer patients over time is changing. You would expect the endocrine-resistant, receptor-positive breast cancer to recur earlier, so those women are removed from the denominator.

If you have a sensitive population and an insensitive population with hormone receptor-positive tumors — even with no difference in efficacy between the hormonal therapies — you should expect to see an increasing effect the later in time you initiate the therapy. However, it’s hard to have a drug that’s so effective down the road that you are able to regain the loss of two to three absolute percentage points that women may experience when the drug is used in this context.

![]() DR LOVE: If you were to treat 100 postmenopausal women, what prescription

would they likely receive before leaving your office?

DR LOVE: If you were to treat 100 postmenopausal women, what prescription

would they likely receive before leaving your office?

![]() DR CARLSON: The vast majority would walk out with a prescription for an

aromatase inhibitor — usually anastrozole in my practice. We have to establish

a practice pattern, and mine is to lead with an aromatase inhibitor. It is

interesting how expert panels interpreted the emerging aromatase inhibitor

data differently. Within 10 to 14 days of the initial ATAC presentation, the

NCCN panel had modified the guidelines to allow anastrozole as an alternative

to tamoxifen as initial hormonal therapy for postmenopausal patients with

ER-positive disease.

DR CARLSON: The vast majority would walk out with a prescription for an

aromatase inhibitor — usually anastrozole in my practice. We have to establish

a practice pattern, and mine is to lead with an aromatase inhibitor. It is

interesting how expert panels interpreted the emerging aromatase inhibitor

data differently. Within 10 to 14 days of the initial ATAC presentation, the

NCCN panel had modified the guidelines to allow anastrozole as an alternative

to tamoxifen as initial hormonal therapy for postmenopausal patients with

ER-positive disease.

The ASCO panel initially believed that tamoxifen should remain the standard hormonal therapy, but that guideline, over time, has also changed. Currently, the NCCN and the ASCO guidelines are essentially identical in terms of up-front hormonal therapy.

Track 5

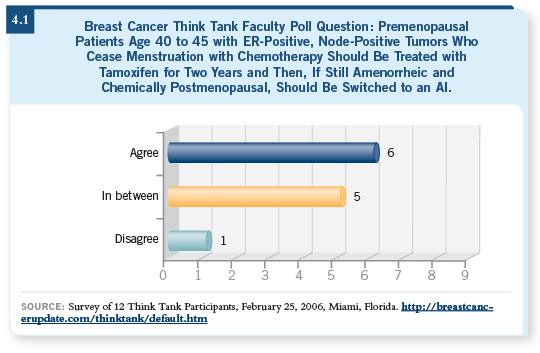

![]() DR LOVE: Do you agree or disagree (4.1): “Premenopausal patients aged

40 to 45 with ER-positive, node-positive tumors who cease menstruation

with chemotherapy should be treated with tamoxifen for two years

and then, if still amenorrheic and chemically postmenopausal, should be

switched to an aromatase inhibitor.”

DR LOVE: Do you agree or disagree (4.1): “Premenopausal patients aged

40 to 45 with ER-positive, node-positive tumors who cease menstruation

with chemotherapy should be treated with tamoxifen for two years

and then, if still amenorrheic and chemically postmenopausal, should be

switched to an aromatase inhibitor.”

![]() DR CARLSON: I would feel comfortable switching a woman in that situation

to an aromatase inhibitor based on the trial data that we have. The difficulty

with that statement, of course, is that the crossover trials, the switching trials,

did not include such women. The women had to be postmenopausal at the

time of diagnosis. So one issue is how biologically similar we think women

are who have gone through chemically induced menopause to those who are

naturally postmenopausal at the time of diagnosis.

DR CARLSON: I would feel comfortable switching a woman in that situation

to an aromatase inhibitor based on the trial data that we have. The difficulty

with that statement, of course, is that the crossover trials, the switching trials,

did not include such women. The women had to be postmenopausal at the

time of diagnosis. So one issue is how biologically similar we think women

are who have gone through chemically induced menopause to those who are

naturally postmenopausal at the time of diagnosis.

![]() DR LOVE: Do you usually switch such patients to an aromatase inhibitor?

DR LOVE: Do you usually switch such patients to an aromatase inhibitor?

![]() DR CARLSON: It is a strategy that I have used. More commonly, I tend to

administer a full five years of tamoxifen and then cross over to letrozole, as

in the MA17 trial (Goss 2005). The MA17 trial eligibility criteria did allow

women who had become postmenopausal during the five years of tamoxifen.

DR CARLSON: It is a strategy that I have used. More commonly, I tend to

administer a full five years of tamoxifen and then cross over to letrozole, as

in the MA17 trial (Goss 2005). The MA17 trial eligibility criteria did allow

women who had become postmenopausal during the five years of tamoxifen.

![]() DR LOVE: What about a patient with 10 positive nodes? Would you still keep

the tamoxifen going for five years?

DR LOVE: What about a patient with 10 positive nodes? Would you still keep

the tamoxifen going for five years?

![]() DR CARLSON: The higher the risk for recurrence, the more willing I would

be to consider crossover to an aromatase inhibitor earlier. That’s not necessarily

logical because my confidence level doesn’t increase in that situation.

DR CARLSON: The higher the risk for recurrence, the more willing I would

be to consider crossover to an aromatase inhibitor earlier. That’s not necessarily

logical because my confidence level doesn’t increase in that situation.

![]() DR LOVE: Obviously the concern is that if the woman were to start menstruating

again, you’d then have an ineffective therapy. The other option is, at

some point, even at the beginning, to include an LHRH agonist or remove

the ovaries — even if the woman has stopped menstruating — just to be sure.

DR LOVE: Obviously the concern is that if the woman were to start menstruating

again, you’d then have an ineffective therapy. The other option is, at

some point, even at the beginning, to include an LHRH agonist or remove

the ovaries — even if the woman has stopped menstruating — just to be sure.

![]() DR CARLSON: That’s an option. The important point, however, that you’re

raising indirectly is that of the women who you believe have become

postmenopausal, secondary to adjuvant chemotherapy, many will experience a resumption of ovarian function. In that context, if you’re going to use

an aromatase inhibitor, you must be confident not only that the woman is

postmenopausal when you start it but also that she remains so as the treatment

is continued.

DR CARLSON: That’s an option. The important point, however, that you’re

raising indirectly is that of the women who you believe have become

postmenopausal, secondary to adjuvant chemotherapy, many will experience a resumption of ovarian function. In that context, if you’re going to use

an aromatase inhibitor, you must be confident not only that the woman is

postmenopausal when you start it but also that she remains so as the treatment

is continued.

Track 7

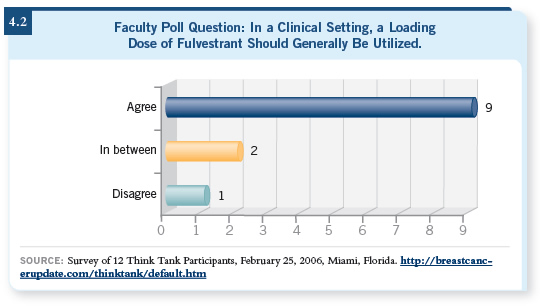

![]() DR LOVE: Do you agree or disagree with the following statement: “In a

clinical setting, a loading dose of fulvestrant generally should be used.”

DR LOVE: Do you agree or disagree with the following statement: “In a

clinical setting, a loading dose of fulvestrant generally should be used.”

![]() DR CARLSON: I agree.

DR CARLSON: I agree.

![]() DR LOVE: Is that something you do in your practice?

DR LOVE: Is that something you do in your practice?

![]() DR CARLSON: Yes, it is.

DR CARLSON: Yes, it is.

![]() DR LOVE: We’re seeing a lot of that from both investigators and oncologists in

practice (4.2). Where do you think we are heading with fulvestrant in terms

of dose and schedule and use for premenopausal women?

DR LOVE: We’re seeing a lot of that from both investigators and oncologists in

practice (4.2). Where do you think we are heading with fulvestrant in terms

of dose and schedule and use for premenopausal women?

![]() DR CARLSON: I continue to see an increase in the number of patients treated

with fulvestrant. That’s reasonable, and experience has confirmed the tolerability

of the drug and the efficacy of the therapy. My expectation is we’ll see

nothing but increased use of fulvestrant. In terms of use for the premenopausal

woman, I believe that in the metastatic setting, we will see increasing numbers

of patients treated with fulvestrant after they are put in a menopausal state. In

part this is because I believe the truly limited number of endocrine agents we

have available for the treatment of premenopausal breast cancer means that,

functionally, after a premenopausal woman has been treated with tamoxifen,

you’re obligated to make her postmenopausal.

DR CARLSON: I continue to see an increase in the number of patients treated

with fulvestrant. That’s reasonable, and experience has confirmed the tolerability

of the drug and the efficacy of the therapy. My expectation is we’ll see

nothing but increased use of fulvestrant. In terms of use for the premenopausal

woman, I believe that in the metastatic setting, we will see increasing numbers

of patients treated with fulvestrant after they are put in a menopausal state. In

part this is because I believe the truly limited number of endocrine agents we

have available for the treatment of premenopausal breast cancer means that,

functionally, after a premenopausal woman has been treated with tamoxifen,

you’re obligated to make her postmenopausal.

Once she’s postmenopausal, the whole spectrum of endocrine agents, which are effective in the postmenopausal woman, become available.

![]() DR LOVE: Do you have patients who are on an LHRH agonist and fulvestrant?

DR LOVE: Do you have patients who are on an LHRH agonist and fulvestrant?

![]() DR CARLSON: In the metastatic setting. Because my expectation is that the

women will be on hormone therapy for some length of time, I often send

those women to the gynecologic oncologist for a laparoscopic oophorectomy.

DR CARLSON: In the metastatic setting. Because my expectation is that the

women will be on hormone therapy for some length of time, I often send

those women to the gynecologic oncologist for a laparoscopic oophorectomy.

Track 11

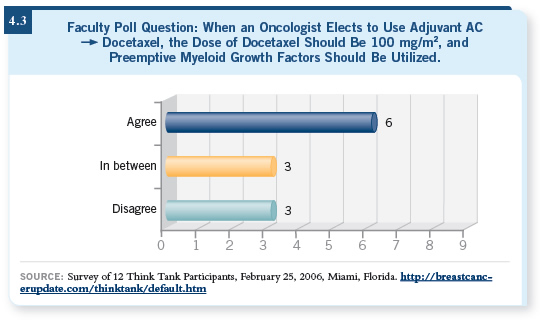

![]() DR LOVE: Here is another Think Tank poll question (4.3). “Putting

cost and reimbursement issues aside, do you agree or disagree that if an

oncologist elects to use adjuvant AC followed by docetaxel, the dose

of docetaxel should be 100 mg/m2 — every three weeks — and that

preemptive myeloid growth factor should be used?”

DR LOVE: Here is another Think Tank poll question (4.3). “Putting

cost and reimbursement issues aside, do you agree or disagree that if an

oncologist elects to use adjuvant AC followed by docetaxel, the dose

of docetaxel should be 100 mg/m2 — every three weeks — and that

preemptive myeloid growth factor should be used?”

![]() DR CARLSON: Docetaxel administered every three weeks at 100 mg/m2 is

a reasonable taxane to use following AC chemotherapy. I have no difficulty

with that. ECOG trial E1199 suggested equal efficacy to paclitaxel in that

setting (Sparano 2005). Perhaps a little more toxicity, especially febrile neutropenia,

occurred with the every three-week regimen. Given the increased

frequency of febrile neutropenia, growth factors would be reasonable to use

with that dose and schedule.

DR CARLSON: Docetaxel administered every three weeks at 100 mg/m2 is

a reasonable taxane to use following AC chemotherapy. I have no difficulty

with that. ECOG trial E1199 suggested equal efficacy to paclitaxel in that

setting (Sparano 2005). Perhaps a little more toxicity, especially febrile neutropenia,

occurred with the every three-week regimen. Given the increased

frequency of febrile neutropenia, growth factors would be reasonable to use

with that dose and schedule.

![]() DR LOVE: Gary Lyman has data suggesting a surprising lack of use of preemptive

growth factors in the adjuvant setting (Lyman 2003). I thought everyone

knew you had to give growth factors when you use TAC. According to him,

a significant number of patients are being treated with adjuvant TAC without

growth factors. Any take on what’s going on?

DR LOVE: Gary Lyman has data suggesting a surprising lack of use of preemptive

growth factors in the adjuvant setting (Lyman 2003). I thought everyone

knew you had to give growth factors when you use TAC. According to him,

a significant number of patients are being treated with adjuvant TAC without

growth factors. Any take on what’s going on?

![]() DR CARLSON: I don’t understand that. TAC certainly causes febrile neutropenia

with high enough frequency that growth factors should be used. The

NCCN Breast Cancer Treatment Guideline specifies the use of growth factors with two of the adjuvant chemotherapy regimens. One would be TAC and the

other would be a dose-dense chemotherapy regimen.

DR CARLSON: I don’t understand that. TAC certainly causes febrile neutropenia

with high enough frequency that growth factors should be used. The

NCCN Breast Cancer Treatment Guideline specifies the use of growth factors with two of the adjuvant chemotherapy regimens. One would be TAC and the

other would be a dose-dense chemotherapy regimen.

Track 12

![]() DR LOVE: Do you agree or disagree? “Patients with strongly ER-positive,

PR-positive, node-positive tumors who require adjuvant therapy should

generally receive TAC chemotherapy as opposed to dose-dense AC

DR LOVE: Do you agree or disagree? “Patients with strongly ER-positive,

PR-positive, node-positive tumors who require adjuvant therapy should

generally receive TAC chemotherapy as opposed to dose-dense AC

![]() paclitaxel and other regimens.”

paclitaxel and other regimens.”

![]() DR CARLSON: One of the difficulties in evaluating the adjuvant therapy

studies and making cross-study comparisons is that the patient populations are

often quite different. The doses and schedules of chemotherapy are almost by

definition different.

DR CARLSON: One of the difficulties in evaluating the adjuvant therapy

studies and making cross-study comparisons is that the patient populations are

often quite different. The doses and schedules of chemotherapy are almost by

definition different.

The analyses of dose-dense chemotherapy and TAC in hormone receptor-positive patients are provocative. Dose-dense chemotherapy showed very little benefit in receptor-positive breast cancer, whereas not much difference in efficacy appeared between the patients with ER-negative and ER-positive disease in the TAC study. Those are indirect comparisons, so I’m not sure we can make much of that specific finding. It’ll be interesting to see, as ECOGE1199 unfolds, if a differential responsiveness appears with docetaxel versus paclitaxel based on ER status, because that’s what you’d have to hypothesize.

![]() DR LOVE: Actually, most oncologists and clinical investigators agree with

you, and they weren’t ready to abandon dose-dense AC

DR LOVE: Actually, most oncologists and clinical investigators agree with

you, and they weren’t ready to abandon dose-dense AC![]() paclitaxel, which,

according to our Patterns of Care studies with both investigators and oncologists,

is by far the most common chemotherapeutic regimen being used for

node-positive disease. The last time I spoke with you, that was your chosen

treatment for patients with node-positive disease. Is that the case?

paclitaxel, which,

according to our Patterns of Care studies with both investigators and oncologists,

is by far the most common chemotherapeutic regimen being used for

node-positive disease. The last time I spoke with you, that was your chosen

treatment for patients with node-positive disease. Is that the case?

![]() DR CARLSON: Yes, and it continues to be the case.

DR CARLSON: Yes, and it continues to be the case.

I’ve been surprised at how nontoxic dose-dense AC followed by paclitaxel is to deliver. You can argue it’s even less toxic and easier to deliver than the every three-week regimens. My experience with TAC is that it’s a difficult regimen. It’s a tolerable regimen — women can get through it — but it’s a much more difficult regimen in terms of acute toxicities.

Track 13

![]() DR LOVE: Do you think that every two-week AC without a taxane with

only growth factor support is a reasonable regimen?

DR LOVE: Do you think that every two-week AC without a taxane with

only growth factor support is a reasonable regimen?

![]() DR CARLSON: It’s a reasonable regimen, and I use it for the patients for whom

I do not consider a taxane necessary. It’s based on the belief — and it’s just

a belief, it’s not yet proven — that if dose-dense AC followed by paclitaxel,

or the ATC dose-dense regimen, is superior, it’s likely that every two-week

AC should be superior, or at least equal to every three-week AC. Again, I’m

impressed at how nontoxic it is when you use growth factors. I believe women

like to get through these therapies quickly, and you shorten the duration of

treatment with the dose-dense regimens.

DR CARLSON: It’s a reasonable regimen, and I use it for the patients for whom

I do not consider a taxane necessary. It’s based on the belief — and it’s just

a belief, it’s not yet proven — that if dose-dense AC followed by paclitaxel,

or the ATC dose-dense regimen, is superior, it’s likely that every two-week

AC should be superior, or at least equal to every three-week AC. Again, I’m

impressed at how nontoxic it is when you use growth factors. I believe women

like to get through these therapies quickly, and you shorten the duration of

treatment with the dose-dense regimens.

Track 14

![]() DR LOVE: Do you agree or disagree with the following statement: “For

patients with minimally symptomatic metastatic breast cancer in nonvisceral

sites, the optimal first-line chemotherapy regimen is single-agent

capecitabine.”

DR LOVE: Do you agree or disagree with the following statement: “For

patients with minimally symptomatic metastatic breast cancer in nonvisceral

sites, the optimal first-line chemotherapy regimen is single-agent

capecitabine.”

![]() DR CARLSON: I would agree with that.

DR CARLSON: I would agree with that.

![]() DR LOVE: For patients with metastatic disease, we are seeing a lot more

earlier use of capecitabine by clinical investigators and breast cancer specialists

compared to those in community practice. In general, is capecitabine your

first-line chemotherapeutic agent?

DR LOVE: For patients with metastatic disease, we are seeing a lot more

earlier use of capecitabine by clinical investigators and breast cancer specialists

compared to those in community practice. In general, is capecitabine your

first-line chemotherapeutic agent?

![]() DR CARLSON: Yes, capecitabine has efficacy that is in the ballpark of any

single agent, and I tend to treat metastatic breast cancer that’s not in visceral

crisis with single-agent therapy. The toxicity profile of capecitabine is favorable,

and the women appreciate being able to take an oral medication, not

having to go to the infusion center and not having to come back as frequently.

It’s an agent that, at doses that are typically used, is associated with a predictable

toxicity experience. I use 1,000 mg/m2 twice daily — two weeks out of

three weeks.

DR CARLSON: Yes, capecitabine has efficacy that is in the ballpark of any

single agent, and I tend to treat metastatic breast cancer that’s not in visceral

crisis with single-agent therapy. The toxicity profile of capecitabine is favorable,

and the women appreciate being able to take an oral medication, not

having to go to the infusion center and not having to come back as frequently.

It’s an agent that, at doses that are typically used, is associated with a predictable

toxicity experience. I use 1,000 mg/m2 twice daily — two weeks out of

three weeks.

![]() DR LOVE: Capecitabine generally doesn’t cause alopecia. How important is

that issue in the metastatic setting?

DR LOVE: Capecitabine generally doesn’t cause alopecia. How important is

that issue in the metastatic setting?

![]() DR CARLSON: That’s very important. If you’re going to use sequential single

agents, it’s always nice to start with an agent that doesn’t cause alopecia. If the

woman already has established alopecia, you don’t gain from the nonalopecia

properties of the new therapy. That’s often an important component of treatment

of metastatic disease.

DR CARLSON: That’s very important. If you’re going to use sequential single

agents, it’s always nice to start with an agent that doesn’t cause alopecia. If the

woman already has established alopecia, you don’t gain from the nonalopecia

properties of the new therapy. That’s often an important component of treatment

of metastatic disease.

The other reason I often will lead with capecitabine is that many of these women, because it’s the first-line therapy, have recently been diagnosed with their metastasis. They will go through all the turmoil and psychic trauma of the new diagnosis, and in that context, often it is easier to start with an agent that has acceptable toxicity, so they can become used to the chronic nature of the disease and the need for ongoing chemotherapy with an agent that has good efficacy and doesn’t affect their quality of life to a major degree.

Track 17

![]() DR LOVE: Do you agree or disagree? “Patients with ER-negative, PRnegative

and HER2-negative tumors (triple negative) should be offered

bevacizumab and chemotherapy in the first-line metastatic setting.”

DR LOVE: Do you agree or disagree? “Patients with ER-negative, PRnegative

and HER2-negative tumors (triple negative) should be offered

bevacizumab and chemotherapy in the first-line metastatic setting.”

![]() DR CARLSON: It’s reasonable to offer such a patient chemotherapy and

bevacizumab. The best evidence we have is with paclitaxel/bevacizumab.

Kathy Miller’s other ECOG study that evaluated capecitabine with or without

bevacizumab showed a slightly higher response rate using the combination

but no advantage in terms of relapse-free survival and overall survival (Miller

2005).

DR CARLSON: It’s reasonable to offer such a patient chemotherapy and

bevacizumab. The best evidence we have is with paclitaxel/bevacizumab.

Kathy Miller’s other ECOG study that evaluated capecitabine with or without

bevacizumab showed a slightly higher response rate using the combination

but no advantage in terms of relapse-free survival and overall survival (Miller

2005).

We may be seeing specific drug effects and different drug interactions between bevacizumab and chemotherapy. It may be a result of different patient populations. The patients in the capecitabine study were treated in the second-line setting, not the first-line setting, as with paclitaxel plus bevacizumab.

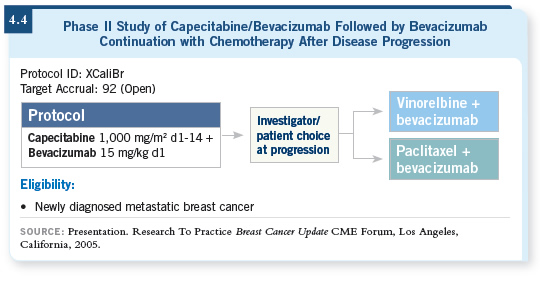

![]() DR LOVE: George Sledge is conducting a study right now of first-line

capecitabine with bevacizumab (4.4).

DR LOVE: George Sledge is conducting a study right now of first-line

capecitabine with bevacizumab (4.4).

![]() DR CARLSON: That’s an important study. Based on the existing data evaluating

capecitabine/bevacizumab, currently I’m not combining bevacizumab

and capecitabine. We didn’t see an advantage and although most patients

tolerate bevacizumab well, it does have toxicity and expense. So I’m limiting

bevacizumab use at the current time to concurrent use with paclitaxel.

DR CARLSON: That’s an important study. Based on the existing data evaluating

capecitabine/bevacizumab, currently I’m not combining bevacizumab

and capecitabine. We didn’t see an advantage and although most patients

tolerate bevacizumab well, it does have toxicity and expense. So I’m limiting

bevacizumab use at the current time to concurrent use with paclitaxel.